438th AAA AW BN

APO 230 % Postmaster, N.Y.

11 March, 1945 0930

Germany

Dearest sweetheart –

An early start on another Sunday morning in Godforsaken Germany. It does my heart good to see the present servility of these people of the Master-race as they drift back to their homes and ask permission to look for this or that and take it with them. I’m called over on all cases as interpreter and when they hear me speak – they jabber on and on about how they didn’t want Hitler, that they’re not Nazis, that they have an uncle or grandmother in Chicago etc. It makes me sick and I tell them I’ve been in Germany about 3½ months and haven’t been able to meet one Nazi – and yet the whole world’s fighting them. They usually get the point then and shut up. As far as I’m concerned they’re all bastards and responsible for my being here.

Today is not exactly a Holiday and yet there’s to be some sort of parade in the big city which you’ve been reading about the past few days. Our outfit – or part of it – is to represent AA of Corps – which is a distinction of one sort or another. I don’t know why they bother to have things like that in the middle of a war – unless it’s to impress the populace. We were supposed to parade after the fall of Cherbourg – but the whole thing was called off at the last minute for some reason not clear to me.

The Colonel got back yesterday – after having had a 7 days’ Leave in London. He flew over and back – leaving from Liège. He seemed to have had a good time and said that London was much more loose and fancy-free than a year ago.

I’ve just re-read your letter of 25 February telling me of the grand day you spent together with Phil and Florence. It was nice of them to have you out with them and it sounded like a swell time – Copley, Ritz, Mayfair – gosh they seem so far away, it’s unbelievable. You get so used to 3 meals a day, drinking liquor raw out of a bottle, wearing the same khaki clothes, no tie, seeing the same all around you – why you just forget about music and dancing and waiters and tablecloths. But it’s going to be so easy to remember again! Don’t get me wrong, darling, I’m not missing that – any of it – except you. And I’m not going to miss it just so long as this war’s on over here. By the way – who were all those Joes you were dancing with? To quote you “as if I’d be jealous!” I hope they didn’t hold you too closely. They’d better not have – because they’ll have me to reckon with once I get back! But I am glad you had a good day and evening and I think it must have done you a lot of good.

I enjoyed your letter telling me about your dream – and me in it, too! It sounded like a natural enough homecoming, sweetheart, and I’m ready for it anytime. I sure wish it were me you were clutching when you awoke instead of that pillow – but it will be I some day! And of course our conversation would be about marriage, and plans etc – rather than about war. I think most of us will be willing to forget about that pronto!

And so now you’re robbing the cradle, are you? Just another example of relativity. That is interesting, though. When you think of it – these young girls being afraid there’ll be no one around for them after the war. I don’t know about no one being around – but I’ll bet the boys will have a lot to pick from. But I don’t see why a girl in her early 20’s has to worry. Anyway, sweetheart, your story made me feel like a gay, young blade – which – in fact – I am!

Yes. I guess I don’t write the folks very much – albeit often. There isn’t a heck of a lot to tell and I certainly don’t discuss the war or any aspect of it with them. Most often – it’s a 3 or 4 line letter saying that all is well – which it is. You admire my disposition about the war, dear, – and I don’t see how anyone can be otherwise. I’ve felt always that it’s tough enough at home – so why make everyone feel worse by griping and complaining? That certainly helps no one and any s-o-b that does it ought to be ashamed of himself. Darling – I’ll save my griping for afterwards – that’s fairer – because then you can gripe right back at me if you have a mind to. Then I can challenge you to a wrestling match – and win of course – because anatomically speaking, I know some swell holds – not to mention certain vital tickling spots. Boy! Oh boy! What you’re in for!

And now I’ll be in for some hell if I don’t see a couple of soldiers on sick-call. So I’ll have to take off again, sweetheart, reminding you it’s only temporary. But my love for you is permanent and that’s what counts. Love to the folks, dear and

An early start on another Sunday morning in Godforsaken Germany. It does my heart good to see the present servility of these people of the Master-race as they drift back to their homes and ask permission to look for this or that and take it with them. I’m called over on all cases as interpreter and when they hear me speak – they jabber on and on about how they didn’t want Hitler, that they’re not Nazis, that they have an uncle or grandmother in Chicago etc. It makes me sick and I tell them I’ve been in Germany about 3½ months and haven’t been able to meet one Nazi – and yet the whole world’s fighting them. They usually get the point then and shut up. As far as I’m concerned they’re all bastards and responsible for my being here.

Today is not exactly a Holiday and yet there’s to be some sort of parade in the big city which you’ve been reading about the past few days. Our outfit – or part of it – is to represent AA of Corps – which is a distinction of one sort or another. I don’t know why they bother to have things like that in the middle of a war – unless it’s to impress the populace. We were supposed to parade after the fall of Cherbourg – but the whole thing was called off at the last minute for some reason not clear to me.

The Colonel got back yesterday – after having had a 7 days’ Leave in London. He flew over and back – leaving from Liège. He seemed to have had a good time and said that London was much more loose and fancy-free than a year ago.

I’ve just re-read your letter of 25 February telling me of the grand day you spent together with Phil and Florence. It was nice of them to have you out with them and it sounded like a swell time – Copley, Ritz, Mayfair – gosh they seem so far away, it’s unbelievable. You get so used to 3 meals a day, drinking liquor raw out of a bottle, wearing the same khaki clothes, no tie, seeing the same all around you – why you just forget about music and dancing and waiters and tablecloths. But it’s going to be so easy to remember again! Don’t get me wrong, darling, I’m not missing that – any of it – except you. And I’m not going to miss it just so long as this war’s on over here. By the way – who were all those Joes you were dancing with? To quote you “as if I’d be jealous!” I hope they didn’t hold you too closely. They’d better not have – because they’ll have me to reckon with once I get back! But I am glad you had a good day and evening and I think it must have done you a lot of good.

Speaking of khaki clothes, Greg received the following rations

on 11 March 1945:

[CLICK TO ENLARGE]

Front and Back

on 11 March 1945:

[CLICK TO ENLARGE]

Front and Back

I enjoyed your letter telling me about your dream – and me in it, too! It sounded like a natural enough homecoming, sweetheart, and I’m ready for it anytime. I sure wish it were me you were clutching when you awoke instead of that pillow – but it will be I some day! And of course our conversation would be about marriage, and plans etc – rather than about war. I think most of us will be willing to forget about that pronto!

And so now you’re robbing the cradle, are you? Just another example of relativity. That is interesting, though. When you think of it – these young girls being afraid there’ll be no one around for them after the war. I don’t know about no one being around – but I’ll bet the boys will have a lot to pick from. But I don’t see why a girl in her early 20’s has to worry. Anyway, sweetheart, your story made me feel like a gay, young blade – which – in fact – I am!

Yes. I guess I don’t write the folks very much – albeit often. There isn’t a heck of a lot to tell and I certainly don’t discuss the war or any aspect of it with them. Most often – it’s a 3 or 4 line letter saying that all is well – which it is. You admire my disposition about the war, dear, – and I don’t see how anyone can be otherwise. I’ve felt always that it’s tough enough at home – so why make everyone feel worse by griping and complaining? That certainly helps no one and any s-o-b that does it ought to be ashamed of himself. Darling – I’ll save my griping for afterwards – that’s fairer – because then you can gripe right back at me if you have a mind to. Then I can challenge you to a wrestling match – and win of course – because anatomically speaking, I know some swell holds – not to mention certain vital tickling spots. Boy! Oh boy! What you’re in for!

And now I’ll be in for some hell if I don’t see a couple of soldiers on sick-call. So I’ll have to take off again, sweetheart, reminding you it’s only temporary. But my love for you is permanent and that’s what counts. Love to the folks, dear and

All my sincerest love,

Greg

* TIDBIT *

about Bombing Essen

and the Story of the Krupp Munitions Family

The Krupp Munitions Plant after 11 March 1945 Bombing

about Bombing Essen

and the Story of the Krupp Munitions Family

The Krupp Munitions Plant after 11 March 1945 Bombing

From LIFE magazine, 4 June 1945, (Vol. 18, No. 23) came this:

So what of the Krupp family?

Published on 5 April 1982 an article in People magazine, (Vol. 17, No. 13), reported this:

As mentioned in the People article, Arndt married Princess Henrietta von Auersperg on February 14, 1969. What the article did not say was that despite this, Arndt was notoriously homosexual. In 1986, four years after the article was written, Arndt - being an alcoholic for a long time - died in his castle in Salzburg of jaw cancer at the age of 48. He was deeply in debt.

A large body of the German munitions plants were located in Essen, a city of 650,000 a few miles north of the Rhine. The heart of this bod was the Krupp Works, Europe's biggest steel plant. Today the city and its heart are a mashed pulp. The picture above shows the center of the Krupp Compound, with wrecked steel mills (foreground) and blasted gas tanks (right background). Most of this damage was done by 500- and 1,000lb. bombs from high altitudes. Despite the raids Alfred Krupp recently claimed his factories were working 50% of capacity until 11 March 1945. On this date 1,000 United States Air Force bombers plastered Essen so thoroughly that even the water supply was cut off. When Americans entered the city seven of Krupp's former 200,000 workers were left in the plant.

So what of the Krupp family?

Published on 5 April 1982 an article in People magazine, (Vol. 17, No. 13), reported this:

Arndt Krupp von Bohlen und Halbach's name evokes images of war and devastation. But the 44-year-old heir to the once-dread munitions empire, is the first Krupp in 171 years to voluntarily lay down his arms. In 1966 Krupp, who has the dubious distinction of being Adolf Hitler's honorary godson, renounced his $500 million inheritance along with the right to take over the Krupp cannon works turned global conglomerate. "I wanted nothing to do with this company," sniffs Arndt. "My father sacrificed his life for work and died a twice-divorced, depressed billionaire. I'm not like him, and I was not interested in his business."

The family began dealing in weapons 11 generations ago in 1587 with a gun-selling store in the Ruhr Valley. Arndt's great-great-grandfather, Alfred ("the Cannon King"), supplied Kaiser Wilhelm armies during the Franco-Prussian War of 1870. Fearing that his workers might organize, Alfred hired an agent to inspect used toilet paper for seditious notes. His son, Fritz, a pudgy sybarite, pyramided Krupp into a world industrial power. When he wasn't building steelworks, Fritz staged Black Masses and homosexual orgies in which skyrockets were fired to celebrate orgasms. When his wife protested, he had her locked up in an asylum. When the scandal broke in the German press, Kaiser Wilhelm II rushed to his support. But it was too late—Fritz committed suicide.

Alfred's daughter, Bertha, inherited the cannonry in 1902 but needed a consort. Hand-picked by the Kaiser, a Prussian diplomat, Gustav von Bohlen und Halbach, was granted the right to use the Krupp name and pass it on to his eldest son. In 1945, not long after Gustav suffered a stroke, that son, Alfried, was arrested and later stood trial at Nuremberg. The Krupp empire was confiscated, and Alfried was sentenced to serve 12 years for the exploitation of some 100,000 people as slave laborers—most of them Jews, many of them women and children. "As a small boy, I went to boarding school near Landsberg Prison so I could see my father," Arndt recalls. "He was unhappy and suffered for crimes committed by Gustav. But my father had no choice. His country was at war, and Hitler told him to make munitions. He had to do it."

Arndt and his mother, whom Alfried had deserted on Gustav's order a few years after their marriage (she was considered too bourgeois to be first lady of Kruppdom), lived hand-to-mouth and were considered pariahs until Alfried's sentence was commuted in 1951 and the company was restored to him. Graduating in the mid-'50s from a Swiss prep school where "boys beat me up because I was a Krupp," Arndt began flaunting his new wealth. He bedecked his playmates, male and female, with lavish jewelry (including a $94,000 Cartier diamond ring) and invited them aboard his 102-foot mahogany yacht, Antinous II, named for the favorite young page of the Roman Emperor Hadrian. "I have a lot of nice lady friends, but I don't exclude the company of men," says Arndt. "I enjoy beauty in every respect, whether it be male or female. In Europe that makes you a playboy."

In 1966, the year Arndt graduated from the University of Cologne, the Krupps hired a Munich public relations man to repair Arndt's image with columnists who had portrayed him as an arrogant Apollo. Finally, in 1969, Arndt decided to marry Princess Henriette "Hettie" von Auersperg of Austria's royal family. These days the couple maintain what Arndt calls "a close friendship" but choose to live apart. Says he: "I love my wife, but we each have strong character traits we need to be alone with.

"My mother has been the closest person to me," Arndt adds. "She was abandoned. I share that with her. It is something special between us." He supervises a staff of 27 servants at his Palm Beach mansion and the family's 84-room Blühnbach Castle in Austria, a 38-room Moroccan palace in Marrakesh and an apartment in Munich.

Through philanthropy, Arndt hopes to redeem his family's tarnished name and give his life meaning. "I want to spend more time in Thailand with underprivileged youth," he says. "I give half a million dollars a year to charity, so I don't feel as bad about spending $100,000 for a car or a piece of jewelry. It soothes the conscience of extravagance."

The Krupp fortune was built in the Franco-Prussian War and two world wars. Forced by the Allies to get out of the weapons business after World War II, the firm, which became a public corporation by 1968, now sells trucks, tools, toys, ships, steel and cement mixers. So why wouldn't the last heir (he has no siblings or offspring) want to rule over the kingdom? "For all my family's money," says the delicate, soft-spoken Arndt, "it didn't always bring them happiness."

Arndt is hardly suffering for his decision. At 28, he began to receive an allowance of $250,000 a year. That figure doubled when his father, Alfried, died a year later. After Arndt spurned a career with the firm, the senior Krupp willed his personal $3.5 billion fortune to a German philanthropic foundation and created a private income for his high-living son, who Alfried knew would never work. In addition to his allowance, Arndt receives a 2.5 percent royalty on each ton of coal produced by a former Krupp mine, plus a percentage of the profits from family-owned supermarkets and hotels in Munich and worldwide real estate holdings. Arndt's worth: "Maybe $80 million, maybe more. I'm not sure."

Two years ago Krupp plunked down a reported $1.5 million for the 26-room Palm Beach villa he now shares with his mother, Annelise. "I hate Germany," he huffs. "I must hide my wealth there. People threw rotten eggs at my Rolls-Royce and made fun of me when I wore expensive jewels." He claims things like that don't happen in Palm Beach—one reason he is applying for U.S. citizenship. "America is the last bastion of freedom," declares the man whose father armed Hitler's war machine. "Society here seems to accept me."

In that belief, he just spent $2.5 million renovating his mansion, including the cheeky task of moving the swimming pool from one side of the house to the other. "He has a wonderful sense of humor," says his Palm Beach chum Ann Light, fourth wife of J. Paul Getty. Chimes in millionaire neighbor Robert D.L. Gardiner: "He's fascinating, well-read and a brilliant conversationalist."

The family began dealing in weapons 11 generations ago in 1587 with a gun-selling store in the Ruhr Valley. Arndt's great-great-grandfather, Alfred ("the Cannon King"), supplied Kaiser Wilhelm armies during the Franco-Prussian War of 1870. Fearing that his workers might organize, Alfred hired an agent to inspect used toilet paper for seditious notes. His son, Fritz, a pudgy sybarite, pyramided Krupp into a world industrial power. When he wasn't building steelworks, Fritz staged Black Masses and homosexual orgies in which skyrockets were fired to celebrate orgasms. When his wife protested, he had her locked up in an asylum. When the scandal broke in the German press, Kaiser Wilhelm II rushed to his support. But it was too late—Fritz committed suicide.

|

| Friedrich Alfred Krupp "Felix" (1854-1902) |

|

| Alfred Krupp (1812 - 1837) Arndt's Great-Great-Grandfather |

Alfred's daughter, Bertha, inherited the cannonry in 1902 but needed a consort. Hand-picked by the Kaiser, a Prussian diplomat, Gustav von Bohlen und Halbach, was granted the right to use the Krupp name and pass it on to his eldest son. In 1945, not long after Gustav suffered a stroke, that son, Alfried, was arrested and later stood trial at Nuremberg. The Krupp empire was confiscated, and Alfried was sentenced to serve 12 years for the exploitation of some 100,000 people as slave laborers—most of them Jews, many of them women and children. "As a small boy, I went to boarding school near Landsberg Prison so I could see my father," Arndt recalls. "He was unhappy and suffered for crimes committed by Gustav. But my father had no choice. His country was at war, and Hitler told him to make munitions. He had to do it."

|

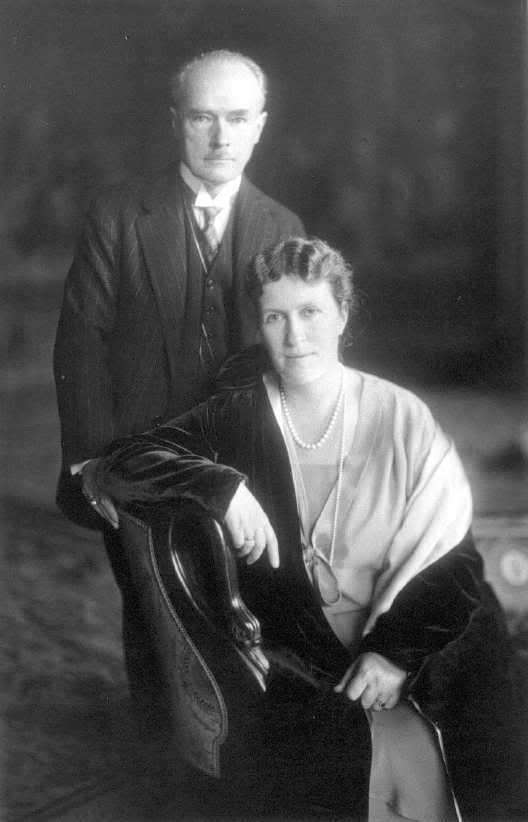

| Gustav and Berta Arndt's Grandparents |

| Alfried Krupp Arndt's Father |

Arndt and his mother, whom Alfried had deserted on Gustav's order a few years after their marriage (she was considered too bourgeois to be first lady of Kruppdom), lived hand-to-mouth and were considered pariahs until Alfried's sentence was commuted in 1951 and the company was restored to him. Graduating in the mid-'50s from a Swiss prep school where "boys beat me up because I was a Krupp," Arndt began flaunting his new wealth. He bedecked his playmates, male and female, with lavish jewelry (including a $94,000 Cartier diamond ring) and invited them aboard his 102-foot mahogany yacht, Antinous II, named for the favorite young page of the Roman Emperor Hadrian. "I have a lot of nice lady friends, but I don't exclude the company of men," says Arndt. "I enjoy beauty in every respect, whether it be male or female. In Europe that makes you a playboy."

In 1966, the year Arndt graduated from the University of Cologne, the Krupps hired a Munich public relations man to repair Arndt's image with columnists who had portrayed him as an arrogant Apollo. Finally, in 1969, Arndt decided to marry Princess Henriette "Hettie" von Auersperg of Austria's royal family. These days the couple maintain what Arndt calls "a close friendship" but choose to live apart. Says he: "I love my wife, but we each have strong character traits we need to be alone with.

"My mother has been the closest person to me," Arndt adds. "She was abandoned. I share that with her. It is something special between us." He supervises a staff of 27 servants at his Palm Beach mansion and the family's 84-room Blühnbach Castle in Austria, a 38-room Moroccan palace in Marrakesh and an apartment in Munich.

Through philanthropy, Arndt hopes to redeem his family's tarnished name and give his life meaning. "I want to spend more time in Thailand with underprivileged youth," he says. "I give half a million dollars a year to charity, so I don't feel as bad about spending $100,000 for a car or a piece of jewelry. It soothes the conscience of extravagance."

The Krupp fortune was built in the Franco-Prussian War and two world wars. Forced by the Allies to get out of the weapons business after World War II, the firm, which became a public corporation by 1968, now sells trucks, tools, toys, ships, steel and cement mixers. So why wouldn't the last heir (he has no siblings or offspring) want to rule over the kingdom? "For all my family's money," says the delicate, soft-spoken Arndt, "it didn't always bring them happiness."

Arndt is hardly suffering for his decision. At 28, he began to receive an allowance of $250,000 a year. That figure doubled when his father, Alfried, died a year later. After Arndt spurned a career with the firm, the senior Krupp willed his personal $3.5 billion fortune to a German philanthropic foundation and created a private income for his high-living son, who Alfried knew would never work. In addition to his allowance, Arndt receives a 2.5 percent royalty on each ton of coal produced by a former Krupp mine, plus a percentage of the profits from family-owned supermarkets and hotels in Munich and worldwide real estate holdings. Arndt's worth: "Maybe $80 million, maybe more. I'm not sure."

Two years ago Krupp plunked down a reported $1.5 million for the 26-room Palm Beach villa he now shares with his mother, Annelise. "I hate Germany," he huffs. "I must hide my wealth there. People threw rotten eggs at my Rolls-Royce and made fun of me when I wore expensive jewels." He claims things like that don't happen in Palm Beach—one reason he is applying for U.S. citizenship. "America is the last bastion of freedom," declares the man whose father armed Hitler's war machine. "Society here seems to accept me."

In that belief, he just spent $2.5 million renovating his mansion, including the cheeky task of moving the swimming pool from one side of the house to the other. "He has a wonderful sense of humor," says his Palm Beach chum Ann Light, fourth wife of J. Paul Getty. Chimes in millionaire neighbor Robert D.L. Gardiner: "He's fascinating, well-read and a brilliant conversationalist."

As mentioned in the People article, Arndt married Princess Henrietta von Auersperg on February 14, 1969. What the article did not say was that despite this, Arndt was notoriously homosexual. In 1986, four years after the article was written, Arndt - being an alcoholic for a long time - died in his castle in Salzburg of jaw cancer at the age of 48. He was deeply in debt.

No comments:

Post a Comment