438th AAA AW BN

APO 230 % Postmaster, N.Y.

Germany

3 November, 1944 1400

My dearest sweetheart –

What with missing one day and writing a short V-mail the next, I really feel as if I’ve been out of touch with you for some time, dear. I got back from my visit to B Battery about noon today and all in all I had a pretty good time. I’ve probably told you before that I like the officers in this battery better than in any other – and that’s why I enjoy visiting them for a few days. They had a pretty good set-up where they were, comfortable, warm and with good beds. We sat around in the evening, listened to the radio and played some cards.

I told you I got back to one of the Belgian cities. I was amazed at the amount of business being done and the variety of articles being sold. There were 2 department stores in town – and the way they fix their windows and display their goods – is really something to see. It just doesn’t seem possible that these people have been in a 5-years war. When you examine the material they are selling, however, you find that most of it is ersatz. Anyway, darling, we did manage to buy a dish of ice-cream and it wasn’t too bad – although it was a far cry from a banana split – for instance.

I returned here to find there had been no mail for anyone for the past 2 days – despite the fact that the Stars and Stripes mentioned the other day that thousands of sacks of mail were arriving in France daily; ours must be on the way. The days roll by and here it is the end of the week again; it doesn’t seem possible that with our being apart so long, sweetheart, that time can be flying by so rapidly. It’s almost a year now – and how I remember my sweating it out back there at Camp Edwards. I’m glad that that is all behind us – but a lot of nice things did happen to us in that time – so we can’t complain too much, dear.

I’ve often thought of that time when it almost seemed as if you’d get down to New York that week-end. Remember you knew someone who lived up on the Hudson near that camp? You guessed correctly – I was at that Camp. At that time I felt that after all – it was best you didn’t come down – but I’ve thought of it countless times since – and I’m sorry you didn’t, sweetheart. You can see now how much every hour – or every evening meant – and you can also see that it wouldn’t have made things any more difficult. The Lord knows, darling, I miss you no less because you stayed away. Oh well – we’ll have that week-end in New York some day and many more too.

The other day – and don’t laugh dear! – I got to thinking of where we might spend our honeymoon. Is that premature wishful thinking? Don’t answer! That’s the truth, though, and you must admit – it’s food for pleasant thought. Although I imagine it’s my duty to think of the place – I’ll tell you now dear – that I’m going to let you decide. I’ve done a lot of traveling in the past couple of years and you can pick the spot you want to go to. Anywhere within reason will be all right with me. As has been said before, it’s wonderful, anywhere.

Yes – I’ve got it all planned out, dear, the clothes I’ll have to buy as soon as I’m out of uniform, getting married, buying a car, furnishing an apartment. I’ve studied my checking account – and you know, sweetheart, – if they’d only end this war – I’m ready to start right now. Maybe I ought to write Gen. Ike. But as Shakespeare wrote – “ … fires burn and cauldrons bubble ” –; we’ll wait until the fire is burnt out and then we’ll have it as we like it.

I’ll close now, dear, and in an hour or so – maybe we’ll have some mail. Until tomorrow, darling, – my love to the folks and

What with missing one day and writing a short V-mail the next, I really feel as if I’ve been out of touch with you for some time, dear. I got back from my visit to B Battery about noon today and all in all I had a pretty good time. I’ve probably told you before that I like the officers in this battery better than in any other – and that’s why I enjoy visiting them for a few days. They had a pretty good set-up where they were, comfortable, warm and with good beds. We sat around in the evening, listened to the radio and played some cards.

I told you I got back to one of the Belgian cities. I was amazed at the amount of business being done and the variety of articles being sold. There were 2 department stores in town – and the way they fix their windows and display their goods – is really something to see. It just doesn’t seem possible that these people have been in a 5-years war. When you examine the material they are selling, however, you find that most of it is ersatz. Anyway, darling, we did manage to buy a dish of ice-cream and it wasn’t too bad – although it was a far cry from a banana split – for instance.

I returned here to find there had been no mail for anyone for the past 2 days – despite the fact that the Stars and Stripes mentioned the other day that thousands of sacks of mail were arriving in France daily; ours must be on the way. The days roll by and here it is the end of the week again; it doesn’t seem possible that with our being apart so long, sweetheart, that time can be flying by so rapidly. It’s almost a year now – and how I remember my sweating it out back there at Camp Edwards. I’m glad that that is all behind us – but a lot of nice things did happen to us in that time – so we can’t complain too much, dear.

I’ve often thought of that time when it almost seemed as if you’d get down to New York that week-end. Remember you knew someone who lived up on the Hudson near that camp? You guessed correctly – I was at that Camp. At that time I felt that after all – it was best you didn’t come down – but I’ve thought of it countless times since – and I’m sorry you didn’t, sweetheart. You can see now how much every hour – or every evening meant – and you can also see that it wouldn’t have made things any more difficult. The Lord knows, darling, I miss you no less because you stayed away. Oh well – we’ll have that week-end in New York some day and many more too.

The other day – and don’t laugh dear! – I got to thinking of where we might spend our honeymoon. Is that premature wishful thinking? Don’t answer! That’s the truth, though, and you must admit – it’s food for pleasant thought. Although I imagine it’s my duty to think of the place – I’ll tell you now dear – that I’m going to let you decide. I’ve done a lot of traveling in the past couple of years and you can pick the spot you want to go to. Anywhere within reason will be all right with me. As has been said before, it’s wonderful, anywhere.

Yes – I’ve got it all planned out, dear, the clothes I’ll have to buy as soon as I’m out of uniform, getting married, buying a car, furnishing an apartment. I’ve studied my checking account – and you know, sweetheart, – if they’d only end this war – I’m ready to start right now. Maybe I ought to write Gen. Ike. But as Shakespeare wrote – “ … fires burn and cauldrons bubble ” –; we’ll wait until the fire is burnt out and then we’ll have it as we like it.

I’ll close now, dear, and in an hour or so – maybe we’ll have some mail. Until tomorrow, darling, – my love to the folks and

All my everlasting love

Greg.

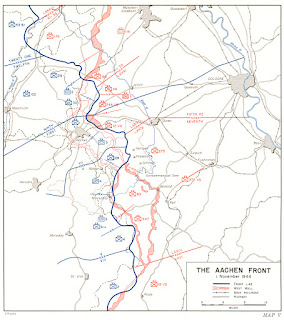

In early September Eisenhower had directed his allied forces to continue attacking on a broad front. His intent was to breech the German frontier and strike deep into Germany. First Army, commanded by General Hodges, would conduct a head-on attack against the Siegfried Line, penetrate and then drive on to the Rhine. Hodges had three Corps within First Army totaling more than 256,000 men. Arrayed north to south on the German frontier (as shown in the above map) was XIX Corps under Major General Charles H. Corlett in the north, VII Corps under Major General J. Lawton Collins in the middle and V Corps under Major General Leonard Gerow to the south.

An article called "Battle of the Huertgen Forest," written by Ernie Herr found on the 5th Armored Division's web site stated this:

An article called "Battle of the Huertgen Forest," written by Ernie Herr found on the 5th Armored Division's web site stated this:

Those that fought the battle from the American side were mostly from the high school classes of 1942, 1943 and 1944. They were to pick up the battle and move on after the classes of 1940 and 1941 had driven this far to the German border but now were too few in numbers to press on. These mostly still teenagers included championship high school football teams, class presidents, those that had sung in the spring concerts, those that were in the class plays, the wizards of the chemistry classes, rich kids, bright kids. There were sergeants with college degrees along with privates from Yale and Harvard. America was throwing her finest young men at the Germans. These youths had come from all sections of the country and from every major ethnic group except the African-American and the Japanese-American.

The training these young men had gone through at State-side posts such as Fort Benning was rigorous physically but severely short on the tactical and leadership challenges that the junior officers would have to meet. British General Horrocks (one of the few generals, if not the only general to do so) made a surprise front line visit to the 84th division and described these young men as "an impressive product of American training methods which turned out division after division complete, fully equipped. The divisions were composed of splendid, very brave, tough young men." But he thought it was too much to ask of green divisions to penetrate strong defense lines, then stand up to counter attacks from first-class German divisions. And he was disturbed by the failure of American division and corps commanders and their staffs to ever visit the front lines. He was greatly concerned to find that the men were not even getting hot meals brought up from the rear, in contrast to the forward divisions in the British line. He reported that not even battalion commanders were going to the front. Senior officers and staff didn't know what they were ordering their rifle companies to do. They did their work from maps and over radios and telephones. And unlike the company and platoon leaders, who had to be replaced every few weeks at best, or every few days at worst, the staff officers took few casualties, so the same men stayed at the same job, doing it badly.

The battle had begun on 19 September 1944 when the 3rd Armored Division and the 9th Infantry Division moved into the forest. The lieutenants and captains had quickly learned that control of formations larger than platoons was nearly impossible. Troops more that a few feet apart couldn't see each other. There were no clearings, only narrow firebreaks and trails. Maps were almost useless. With air support and artillery also nearly useless, the GIs were committed to a fight of mud and mines, carried out by infantry skirmish lines plunging ever deeper into the forest, with machine guns and light mortars their only support. For the GIs, it was a calamity. In the September-October action, the 9th and 2nd Armored Divisions lost up to 80 percent of their front-line troops, and gained almost nothing.

On November 2, the 28th Infantry Division took up the fight. The 28th was the Pennsylvania National Guard and was called the "Keystone Division" referring to their red keystone shoulder patch. So many of the Pennsylvania National Guard were to fall here that the Germans referred to them as the "Bloody Bucket Division," since the keystone looked somewhat like a bucket.

When the 28th tried to move forward, it was like walking into hell. From their bunkers, the Germans sent forth a hail of machine-gun and rifle fire and mortars. The GIs were caught in thick minefields. Their attack stalled. For two weeks, the 28th kept attacking, as ordered.

On November 5, division sent down orders to move tanks down a road called the Kall Trail. But, as usual, no staff officer had gone forward to assess the situation in person, and in fact the "trail" was solid mud blocked by felled trees and disabled tanks. The attack led only to more heavy loss of life. The 28th's lieutenants kept leading. By November 13, all the officers in the rifle companies had been killed or wounded. Most of them were within a year of their twentieth birthday. Overall in the Huertgen, the 28th suffered 6,184 combat casualties, plus 738 cases of trench foot and 620 battle fatigue cases. Those figures meant that virtually every front-line soldier was a casualty. The 28th Division had essentially been wiped out.

The training these young men had gone through at State-side posts such as Fort Benning was rigorous physically but severely short on the tactical and leadership challenges that the junior officers would have to meet. British General Horrocks (one of the few generals, if not the only general to do so) made a surprise front line visit to the 84th division and described these young men as "an impressive product of American training methods which turned out division after division complete, fully equipped. The divisions were composed of splendid, very brave, tough young men." But he thought it was too much to ask of green divisions to penetrate strong defense lines, then stand up to counter attacks from first-class German divisions. And he was disturbed by the failure of American division and corps commanders and their staffs to ever visit the front lines. He was greatly concerned to find that the men were not even getting hot meals brought up from the rear, in contrast to the forward divisions in the British line. He reported that not even battalion commanders were going to the front. Senior officers and staff didn't know what they were ordering their rifle companies to do. They did their work from maps and over radios and telephones. And unlike the company and platoon leaders, who had to be replaced every few weeks at best, or every few days at worst, the staff officers took few casualties, so the same men stayed at the same job, doing it badly.

The battle had begun on 19 September 1944 when the 3rd Armored Division and the 9th Infantry Division moved into the forest. The lieutenants and captains had quickly learned that control of formations larger than platoons was nearly impossible. Troops more that a few feet apart couldn't see each other. There were no clearings, only narrow firebreaks and trails. Maps were almost useless. With air support and artillery also nearly useless, the GIs were committed to a fight of mud and mines, carried out by infantry skirmish lines plunging ever deeper into the forest, with machine guns and light mortars their only support. For the GIs, it was a calamity. In the September-October action, the 9th and 2nd Armored Divisions lost up to 80 percent of their front-line troops, and gained almost nothing.

On November 2, the 28th Infantry Division took up the fight. The 28th was the Pennsylvania National Guard and was called the "Keystone Division" referring to their red keystone shoulder patch. So many of the Pennsylvania National Guard were to fall here that the Germans referred to them as the "Bloody Bucket Division," since the keystone looked somewhat like a bucket.

When the 28th tried to move forward, it was like walking into hell. From their bunkers, the Germans sent forth a hail of machine-gun and rifle fire and mortars. The GIs were caught in thick minefields. Their attack stalled. For two weeks, the 28th kept attacking, as ordered.

On November 5, division sent down orders to move tanks down a road called the Kall Trail. But, as usual, no staff officer had gone forward to assess the situation in person, and in fact the "trail" was solid mud blocked by felled trees and disabled tanks. The attack led only to more heavy loss of life. The 28th's lieutenants kept leading. By November 13, all the officers in the rifle companies had been killed or wounded. Most of them were within a year of their twentieth birthday. Overall in the Huertgen, the 28th suffered 6,184 combat casualties, plus 738 cases of trench foot and 620 battle fatigue cases. Those figures meant that virtually every front-line soldier was a casualty. The 28th Division had essentially been wiped out.