438th AAA AW BN

APO 527 % Postmaster, N.Y.

England

19 February, 1944 0930

Dearest sweetheart –

Saturday morning has become inspection morning once more. There was a time when it was felt that once overseas – we could do without the pomp and circumstance that we had in garrison back home. But here we are having it again. I suppose if we ever get to some real front lines – action will have to stop on Saturday mornings to allow inspecting officers to come around. We’ve already been inspected this morning, dear, and everything was found to be all right. They don’t usually bother us very much, anyway – but it’s the idea of it that I don’t like. Oh well – enough of that.

The Saturdays really do roll along. Despite almost 20 months of being in the Army and having one day just like the other, I still can’t shake that feeling of having done something a little bit different on the week-end. I don’t suppose I’ll ever lose that feeling, darling, and it’s just as well.

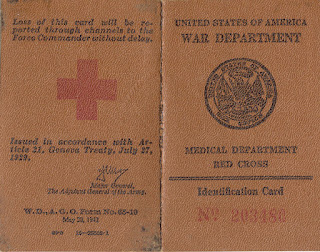

In that connection, dear, – you ask me to write more about my activity. Do you mean what the outfit is doing etc. – or my own.? I think you refer to the latter – but I don’t know what more I can write you, Sweetheart, beyond which I already have. The sum and substance of it is that I just don’t have any activity – and limited as yours has been, dear, I can assure you that mine is even more so. Don’t forget I don’t have friends, relatives, etc. to call on the phone. The only familiar faces I see are those of the soldiers around me. And when I’m blue, dear, I don’t have my mother and father to talk things over with. I’m not complaining though, because our position could be so much worse! But getting back to my activity, in sum and substance it goes somewhat like this: breakfast between 0700 and 0730; listen to BBC at 0800 – news; shave 0830+; sick-call 0900 and generally over about 1000; visit gun section 1000-1200 and then lunch. After lunch, darling, I’ve been writing you and then at 1400 I’ve been teaching first aid, medicine etc. until about 1530-1600; between 1600-1700 I usually do some reading or check up on our reports or some such thing. At 1700 we eat and from then on we hang around in quarters. I’ve told you what that amounts to, already. How does this program vary? It doesn’t very much, dear – but occasionally we go to a movie or some U.S.O. or special service program on the post. Our time off is 48 hours about every 2 weeks – I went 3 weeks ago and as yet have nothing in view to make me go again. Once you miss the pass, it’s missed, dear – so I won’t be going anyway for about another week.

Another question you asked, sweetheart, was whether or not I changed my mind about going out. Darling – it isn’t a question of changing my mind at all. I didn’t make up my mind about not going out with girls. I knew I didn’t want to, I had no desire to and what’s more dear – that’s the way I still feel and I know I’ll continue to feel that way. I just can’t conceive of being with anyone else but you, darling. I couldn’t be hearing from you daily and writing you as often as I can – and feel otherwise. You and only you, dearest are my main theme and you are the only one who interests me.

I got two letters from Eleanor yesterday, one from my brother and two cards from my father – one from N.Y., the other from Pittsburgh. I hadn’t known he was on his way to Ohio. Eleanor wrote me about my bank balance and that my government checks were arriving on schedule. Lawrence wrote me about school, etc.

And so there you are, dear. That’s about all for now – but I do hope the mail situation has straightened out for you. You must by now have received a whole batch of my letters. Your inability to ration them is like mine. I just can’t wait and I read them all when they arrive. I love to have you tell me you love me, darling, and I love to tell you the same. How am I doing in that respect? At any rate – you must know I do – and how much. I want you to always remember that, dear, until I can prove it to you in person. So long for now, sweetheart and for now

Saturday morning has become inspection morning once more. There was a time when it was felt that once overseas – we could do without the pomp and circumstance that we had in garrison back home. But here we are having it again. I suppose if we ever get to some real front lines – action will have to stop on Saturday mornings to allow inspecting officers to come around. We’ve already been inspected this morning, dear, and everything was found to be all right. They don’t usually bother us very much, anyway – but it’s the idea of it that I don’t like. Oh well – enough of that.

The Saturdays really do roll along. Despite almost 20 months of being in the Army and having one day just like the other, I still can’t shake that feeling of having done something a little bit different on the week-end. I don’t suppose I’ll ever lose that feeling, darling, and it’s just as well.

In that connection, dear, – you ask me to write more about my activity. Do you mean what the outfit is doing etc. – or my own.? I think you refer to the latter – but I don’t know what more I can write you, Sweetheart, beyond which I already have. The sum and substance of it is that I just don’t have any activity – and limited as yours has been, dear, I can assure you that mine is even more so. Don’t forget I don’t have friends, relatives, etc. to call on the phone. The only familiar faces I see are those of the soldiers around me. And when I’m blue, dear, I don’t have my mother and father to talk things over with. I’m not complaining though, because our position could be so much worse! But getting back to my activity, in sum and substance it goes somewhat like this: breakfast between 0700 and 0730; listen to BBC at 0800 – news; shave 0830+; sick-call 0900 and generally over about 1000; visit gun section 1000-1200 and then lunch. After lunch, darling, I’ve been writing you and then at 1400 I’ve been teaching first aid, medicine etc. until about 1530-1600; between 1600-1700 I usually do some reading or check up on our reports or some such thing. At 1700 we eat and from then on we hang around in quarters. I’ve told you what that amounts to, already. How does this program vary? It doesn’t very much, dear – but occasionally we go to a movie or some U.S.O. or special service program on the post. Our time off is 48 hours about every 2 weeks – I went 3 weeks ago and as yet have nothing in view to make me go again. Once you miss the pass, it’s missed, dear – so I won’t be going anyway for about another week.

Another question you asked, sweetheart, was whether or not I changed my mind about going out. Darling – it isn’t a question of changing my mind at all. I didn’t make up my mind about not going out with girls. I knew I didn’t want to, I had no desire to and what’s more dear – that’s the way I still feel and I know I’ll continue to feel that way. I just can’t conceive of being with anyone else but you, darling. I couldn’t be hearing from you daily and writing you as often as I can – and feel otherwise. You and only you, dearest are my main theme and you are the only one who interests me.

I got two letters from Eleanor yesterday, one from my brother and two cards from my father – one from N.Y., the other from Pittsburgh. I hadn’t known he was on his way to Ohio. Eleanor wrote me about my bank balance and that my government checks were arriving on schedule. Lawrence wrote me about school, etc.

And so there you are, dear. That’s about all for now – but I do hope the mail situation has straightened out for you. You must by now have received a whole batch of my letters. Your inability to ration them is like mine. I just can’t wait and I read them all when they arrive. I love to have you tell me you love me, darling, and I love to tell you the same. How am I doing in that respect? At any rate – you must know I do – and how much. I want you to always remember that, dear, until I can prove it to you in person. So long for now, sweetheart and for now

All my love

Greg

Regards to the family

Love

G.