438th AAA AW BN

APO 527 % Postmaster, N.Y.

England

7 March, 1944 1100

Dearest darling Wilma –

Today is four months since I last saw you, talked with you, kissed you. Actually a third of a year has slipped by, sweetheart, and yet I’m not impressed with the time interval, probably because I feel I’ve gotten to know you so much better during these past few months. In other words – what has happened, dear, is what I wanted to happen – not a big lapse by my leaving, but a normal development of our affection. I hope darling, that you feel the same way. How many more months it will take before I can fulfill my affection – the Lord alone knows, but as they say in the Army, dear – I can sweat it out and I’m counting on you.

Well – here it is the last day but one of my leave. Tomorrow, dear, I’ll be heading back and so I probably won’t get a chance to write. With this letter, darling, I will have written you five times out of my seven days, which isn’t bad considering traveling. The fact is – I just don’t feel right unless I do write you a few lines.

Yesterday, Sweetheart, I headed for the Strand – which is this City’s equivalent of the show district in New York. On the way – I passed Fleet St. which is a famous old street where most of the newspapers in England are printed. I finally got to the Aldwych theater where the Lunts were playing. There was a sign saying advance sale only – but I got into the queue and calmly asked for a seat for that night. I was amazed when I was offered a ticket in the 14th row – orchestra – which they call the Stalls. The price, by the way, was 13 – 6 or about $2.70. The first balcony – which they call Dress Circle and which for some ridiculous reason is considered the best seat – be it for Symphony, movie or theater – costs 22 shillings – or $4.40.

The play started at 1715 – all the shows here start very early evening to allow people to get out by 2000 or so – so that they can get home before any trouble starts. About the play – it was Robt. E. Sherwood’s “There Shall Be No Night” – and Sweetheart, it was superb. I believe it played in N.Y. but it must be appreciated much more here where people have suffered more – from the horrors of war. The dialogue was excellent – and I don’t see how anyone could have done better with it than Lynn Fontaine and Alfred Lunt. The theme deals with the Greeks in Athens right before the Italians and then the Germans marched in to ruin things.

Now – today, dear, I have yet to see the famous Wax Museum and I definitely plan to take that in this p.m.

I’m anxious, darling, to get back to Camp because I know there must be a few letters waiting for me, from you. I’ll probably be busy the next couple of weeks – because Charlie goes on his leave as soon as I get back – and then our dentist goes, so I’ll have to travel around a bit to keep things covered.

I wonder how things are with you darling, and your folks – and everything. I just can’t tell you in words, dear, how much you’ve come to mean to me in my every thought and plan of the future. You’ve become so much an integral part of me that I wonder what being here – without knowing and loving you – would have been. I’m glad I don’t have to know the answer to that. All I know is that I love you so very much that I’m able to live in the future, darling. The present would be very bleak to fall back on – believe me. I’ll close now, Sweetheart. Best regards home and you have –

Today is four months since I last saw you, talked with you, kissed you. Actually a third of a year has slipped by, sweetheart, and yet I’m not impressed with the time interval, probably because I feel I’ve gotten to know you so much better during these past few months. In other words – what has happened, dear, is what I wanted to happen – not a big lapse by my leaving, but a normal development of our affection. I hope darling, that you feel the same way. How many more months it will take before I can fulfill my affection – the Lord alone knows, but as they say in the Army, dear – I can sweat it out and I’m counting on you.

Well – here it is the last day but one of my leave. Tomorrow, dear, I’ll be heading back and so I probably won’t get a chance to write. With this letter, darling, I will have written you five times out of my seven days, which isn’t bad considering traveling. The fact is – I just don’t feel right unless I do write you a few lines.

Yesterday, Sweetheart, I headed for the Strand – which is this City’s equivalent of the show district in New York. On the way – I passed Fleet St. which is a famous old street where most of the newspapers in England are printed. I finally got to the Aldwych theater where the Lunts were playing. There was a sign saying advance sale only – but I got into the queue and calmly asked for a seat for that night. I was amazed when I was offered a ticket in the 14th row – orchestra – which they call the Stalls. The price, by the way, was 13 – 6 or about $2.70. The first balcony – which they call Dress Circle and which for some ridiculous reason is considered the best seat – be it for Symphony, movie or theater – costs 22 shillings – or $4.40.

The play started at 1715 – all the shows here start very early evening to allow people to get out by 2000 or so – so that they can get home before any trouble starts. About the play – it was Robt. E. Sherwood’s “There Shall Be No Night” – and Sweetheart, it was superb. I believe it played in N.Y. but it must be appreciated much more here where people have suffered more – from the horrors of war. The dialogue was excellent – and I don’t see how anyone could have done better with it than Lynn Fontaine and Alfred Lunt. The theme deals with the Greeks in Athens right before the Italians and then the Germans marched in to ruin things.

Now – today, dear, I have yet to see the famous Wax Museum and I definitely plan to take that in this p.m.

I’m anxious, darling, to get back to Camp because I know there must be a few letters waiting for me, from you. I’ll probably be busy the next couple of weeks – because Charlie goes on his leave as soon as I get back – and then our dentist goes, so I’ll have to travel around a bit to keep things covered.

I wonder how things are with you darling, and your folks – and everything. I just can’t tell you in words, dear, how much you’ve come to mean to me in my every thought and plan of the future. You’ve become so much an integral part of me that I wonder what being here – without knowing and loving you – would have been. I’m glad I don’t have to know the answer to that. All I know is that I love you so very much that I’m able to live in the future, darling. The present would be very bleak to fall back on – believe me. I’ll close now, Sweetheart. Best regards home and you have –

All my love

Greg

* TIDBIT *

about Aldwych Street and a V-1 Rocket

The Aldwych Theatre

about Aldwych Street and a V-1 Rocket

The Aldwych Theatre

Greg mentioned being in line for tickets to see the Lunts perform in There Shall Be No Night at the Aldwych Theatre. It was still playing on June 30th, when the following story of a V-1 blast at Aldwych Street unfolded, as told in an excerpt from “The Secret Fire” by Martin Langfield (© 2009). The excerpt in the book is based on eye-witness accounts, official reports and contemporary photographs. Some of the original source material for the book came from a website called "BBC's WWII People's War."

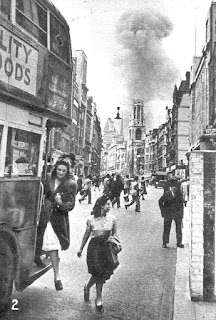

The photos included are from the Imperial War Museum. To hear audio of a V-1 attack, click here.)

The London air raid sirens howled.

The V-1 tore across southern England at over 350 miles per hour, faster than almost anything the British could put in the air against it, skipping past the barrage balloons’ steel cables that were intended to tear off its wings, outpacing all the efforts of the anti-aircraft gunners to traverse their guns fast enough to blow it out of the sky.

On Aldwych, at the eastern end of the Strand, dozens of people queuing outside the Post Office on the ground floor of Bush House looked skywards. Girls on their lunch break at the Air Ministry at Adastral House opposite, sunbathing on the roof, hurriedly covered up.

In the basement of Australia House, just east of the post office, an Australian Mustang pilot named Alan Clark cued up a shot at the snooker table, oblivious of the looming danger overhead.

Double-decker buses let passengers on and off, lined up just east of Kingsway on the semicircular Aldwych kerb.

A black silhouette against the brilliant blue summer sky, the V-1 began its final dive over South London, somewhere above Waterloo Station, the mechanical growl of its pulse-jet engine suddenly cutting off.

Then the dreadful silence as it fell. In the East Court of Bush House, alarm bells rang inside the building, indicating ‘enemy action imminent’. Fourteen year old Derrick Grady and his friends from the post room at the BBC’s Foreign Service, returning to work at Bush House after spending their lunch hour fooling around by Cleopatra’s Needle, saw the dark shape disappear behind the buildings in front of them. They threw themselves to the ground.

Several young women inside the Air Ministry massed at a window, trying to get a look at the ‘ghastly thing’. Some bus passengers tried to take cover. Others in the bus and post office queues trusted to luck or God, resignation and indifference in their faces, knowing that if they heard it explode, they would probably still be alive. Helplessly, they watched it fall towards them.

A young woman at the Air Ministry, chatting with a colleague in their boss’s office, saw the flash of the explosion reflected in her friend’s eyes, a split-second before the deafening blast hit them. The V-1 fell in the middle of the street between Bush House and Adastral House, the home of the Air Ministry, at 2:07 p.m., making a direct hit on one of the city’s main loci of power, the site of the Aldwych holy well, directly on the London ley line. Brilliant blue skies turned to grey fog and darkness.

The device exploded some 40 yards east of the junction of Aldwych and Kingsway, about 40 feet from the Air Ministry offices opposite the east wing of Bush House. As the Australian serviceman took his snooker shot, the plaster ceiling in the basement of Australia House fell in on the table in front of him. The Air Ministry’s 10-foot-tall blast walls, made of 18-inch-thick brick, disintegrated immediately, deflecting the force of the explosion. Hundreds of panes of glass shattered, blowing razor-sharp splinters through the air. The Air Ministry women watching at the windows were sucked out of Adastral House by the vacuum and dashed to death on the street below. Men and women queuing outside the Post Office were torn to pieces. Shrapnel peppered the facades of Bush House and the Air Ministry like bullets.

A double-decker approaching Aldwych reared up like a frightened horse, settled for a brief moment, then veered over at an angle of 45 degrees, first to one side, then to the other. The roof of the bus in front peeled back, as if cut by a giant tin-opener. The other double-deckers waiting on Aldwych were shattered, their red bodywork ripped to pieces, their passengers torn apart. Australia House’s great glass dome shattered, fragments smashing down into the vestibule. Broken panes from all the damaged buildings fell like sleet into the street.

The blast wrecked the facade of the Aldwych Theatre on the corner of Drury Lane, killing an airman at the box-office window as he was buying a ticket for that night’s performance of the anti-totalitarian play There Shall Be No Night by Robert Emmet Sherwood, starring Alfred Lunt and Lynn Fontaine.

Outside Adastral House, a heavy door flew off its hinges, crushing the doorman standing outside. The blast killed all the sunbathing women on the roof of the Air Ministry. Dust and smoke spewed everywhere.

Part of the casement of the bomb lay burning at the corner of Kingsway. The dead and dying lay scattered in the street. Groans and cries of pain filled the air, though many could not hear them, deafened by the concussion. Some of the victims were naked, their clothing blown from them by the blast.

Aldwych was covered in every direction with debris and broken glass. Banknotes blew in the breeze. A private car stood shattered near the twisted remains of an emergency surface water tank, its 11,000 gallons dispersed, the steel sheets of its walls blown apart. People walked around dazed, blood pouring from wounds some didn’t know they had, the crunch of broken glass under their feet ubiquitous. One woman walked down seventy-nine steps of an Adastral House stairwell to the street, not realizing her right foot was hanging sideways, feeling no pain, stepping over bodies.

Staff and guests from the nearby Waldorf Hotel ran to help. Ambulances and fire engines sped to the scene. Police directed the injured to a First Aid post in the basement of Bush House, casualties receiving treatment for the next three hours. Still it was not safe. One man stepped from a doorway after the blast and was sliced vertically in two by a sheet of falling glass. A news editor of the Evening Standard who came upon the scene couldn’t take his eyes off the trees. Their leaves had all been replaced by pieces of human flesh.

Alan Haylock, a Reuter's office boy, who’d been on one of the double-deckers, running to help, came across a middle-aged woman sitting on the pavement, propped up against a shop front, her face deathly white, cuts all about her face and neck, one shoe missing and her stockings torn. She had auburn hair and was still clutching her handbag. He bent down to see if he could help her. Then a voice behind him said: ‘There’s nothing you can do for her, chum. She’s gone. Died about two or three minutes ago.’

Soon the junction of Kingsway and Aldwych was a sea of stretchers, the occupants all dead. Experienced ambulance workers worked in quick and practised drills to remove the dead and seriously hurt. When the counting was done, about fifty people were killed, 400 seriously wounded, another 200 lightly injured.

The V-1 tore across southern England at over 350 miles per hour, faster than almost anything the British could put in the air against it, skipping past the barrage balloons’ steel cables that were intended to tear off its wings, outpacing all the efforts of the anti-aircraft gunners to traverse their guns fast enough to blow it out of the sky.

On Aldwych, at the eastern end of the Strand, dozens of people queuing outside the Post Office on the ground floor of Bush House looked skywards. Girls on their lunch break at the Air Ministry at Adastral House opposite, sunbathing on the roof, hurriedly covered up.

In the basement of Australia House, just east of the post office, an Australian Mustang pilot named Alan Clark cued up a shot at the snooker table, oblivious of the looming danger overhead.

Double-decker buses let passengers on and off, lined up just east of Kingsway on the semicircular Aldwych kerb.

A black silhouette against the brilliant blue summer sky, the V-1 began its final dive over South London, somewhere above Waterloo Station, the mechanical growl of its pulse-jet engine suddenly cutting off.

Then the dreadful silence as it fell. In the East Court of Bush House, alarm bells rang inside the building, indicating ‘enemy action imminent’. Fourteen year old Derrick Grady and his friends from the post room at the BBC’s Foreign Service, returning to work at Bush House after spending their lunch hour fooling around by Cleopatra’s Needle, saw the dark shape disappear behind the buildings in front of them. They threw themselves to the ground.

Several young women inside the Air Ministry massed at a window, trying to get a look at the ‘ghastly thing’. Some bus passengers tried to take cover. Others in the bus and post office queues trusted to luck or God, resignation and indifference in their faces, knowing that if they heard it explode, they would probably still be alive. Helplessly, they watched it fall towards them.

A young woman at the Air Ministry, chatting with a colleague in their boss’s office, saw the flash of the explosion reflected in her friend’s eyes, a split-second before the deafening blast hit them. The V-1 fell in the middle of the street between Bush House and Adastral House, the home of the Air Ministry, at 2:07 p.m., making a direct hit on one of the city’s main loci of power, the site of the Aldwych holy well, directly on the London ley line. Brilliant blue skies turned to grey fog and darkness.

The device exploded some 40 yards east of the junction of Aldwych and Kingsway, about 40 feet from the Air Ministry offices opposite the east wing of Bush House. As the Australian serviceman took his snooker shot, the plaster ceiling in the basement of Australia House fell in on the table in front of him. The Air Ministry’s 10-foot-tall blast walls, made of 18-inch-thick brick, disintegrated immediately, deflecting the force of the explosion. Hundreds of panes of glass shattered, blowing razor-sharp splinters through the air. The Air Ministry women watching at the windows were sucked out of Adastral House by the vacuum and dashed to death on the street below. Men and women queuing outside the Post Office were torn to pieces. Shrapnel peppered the facades of Bush House and the Air Ministry like bullets.

A double-decker approaching Aldwych reared up like a frightened horse, settled for a brief moment, then veered over at an angle of 45 degrees, first to one side, then to the other. The roof of the bus in front peeled back, as if cut by a giant tin-opener. The other double-deckers waiting on Aldwych were shattered, their red bodywork ripped to pieces, their passengers torn apart. Australia House’s great glass dome shattered, fragments smashing down into the vestibule. Broken panes from all the damaged buildings fell like sleet into the street.

The blast wrecked the facade of the Aldwych Theatre on the corner of Drury Lane, killing an airman at the box-office window as he was buying a ticket for that night’s performance of the anti-totalitarian play There Shall Be No Night by Robert Emmet Sherwood, starring Alfred Lunt and Lynn Fontaine.

Outside Adastral House, a heavy door flew off its hinges, crushing the doorman standing outside. The blast killed all the sunbathing women on the roof of the Air Ministry. Dust and smoke spewed everywhere.

Part of the casement of the bomb lay burning at the corner of Kingsway. The dead and dying lay scattered in the street. Groans and cries of pain filled the air, though many could not hear them, deafened by the concussion. Some of the victims were naked, their clothing blown from them by the blast.

Aldwych was covered in every direction with debris and broken glass. Banknotes blew in the breeze. A private car stood shattered near the twisted remains of an emergency surface water tank, its 11,000 gallons dispersed, the steel sheets of its walls blown apart. People walked around dazed, blood pouring from wounds some didn’t know they had, the crunch of broken glass under their feet ubiquitous. One woman walked down seventy-nine steps of an Adastral House stairwell to the street, not realizing her right foot was hanging sideways, feeling no pain, stepping over bodies.

Staff and guests from the nearby Waldorf Hotel ran to help. Ambulances and fire engines sped to the scene. Police directed the injured to a First Aid post in the basement of Bush House, casualties receiving treatment for the next three hours. Still it was not safe. One man stepped from a doorway after the blast and was sliced vertically in two by a sheet of falling glass. A news editor of the Evening Standard who came upon the scene couldn’t take his eyes off the trees. Their leaves had all been replaced by pieces of human flesh.

Alan Haylock, a Reuter's office boy, who’d been on one of the double-deckers, running to help, came across a middle-aged woman sitting on the pavement, propped up against a shop front, her face deathly white, cuts all about her face and neck, one shoe missing and her stockings torn. She had auburn hair and was still clutching her handbag. He bent down to see if he could help her. Then a voice behind him said: ‘There’s nothing you can do for her, chum. She’s gone. Died about two or three minutes ago.’

Soon the junction of Kingsway and Aldwych was a sea of stretchers, the occupants all dead. Experienced ambulance workers worked in quick and practised drills to remove the dead and seriously hurt. When the counting was done, about fifty people were killed, 400 seriously wounded, another 200 lightly injured.

The photos included are from the Imperial War Museum. To hear audio of a V-1 attack, click here.)