438th AAA AW BN

APO 230 % Postmaster, N.Y.

Germany

7 November, 1944 1300

My dearest sweetheart –

I got two swell letters from you yesterday – the only two the medical detachment received – by the way – and I’m getting caught up now a bit on your mail, dear. I hope mine is coming through to you a bit better too. You remark in one of your letters that “so long for now” is a G-I expression, or so you believe. I’ve always used those words, dear, and I don’t think I picked it up in the Army – but I’ve been in so damned long now – I really don’t remember a good many things about my civilian days. Do you realize, sweetheart, that you have never known me as a civilian but only as a soldier? I wonder how you’ll find me? As a matter of fact, I wonder how I’ll find myself. I guess every soldier finds himself thinking about that. It will be strange wearing different colored socks, and a tie around our necks. It’s a year since I’ve had one on – except of course when we had a pass in England. And I’m getting a little tired of this damned brownish-green stuff we wear. Every now and then I open my val-a-pac and air out my pinks and blouse; it’s so darned damp here we have to watch out for molds. They sure look fancy compared to the way we look these days. Now how did I get started on that? I’ll be crying on someone’s shoulder if I don’t stop – and I don’t really feel that way at all. You’ll marry me in uniform too – won’t you dear? I really think that once we get back to the States we’ll be de-mobilized quickly anyway.

I forgot all about the statement of mine concerning AA and the Pacific, dear. I wrote that to your mother and apparently forgot to mention it to you. And it wasn’t just a statement by a yokel – it was made by the commanding General of all AA – who happened to be on a tour over here and visited our battalion. He ought to be in a position to know. There was a time in our early days in Normandy when we were all worrying about that. There was so little of the Luftwaffe around for us to shoot at we figured we might be transferred. But later on we started getting targets and the artillery and infantry have recognized our value, I think. I’m worried more about the possibility of Lawrence having to go to the Pacific theater. I shouldn’t like that at all.

I didn’t know Red Perkins – but it’s a sad tale just the same. It’s the same old story – the folks at home are the ones that catch the most hell. That thought, incidentally dear, has always worried me more than anything else since I’ve been a soldier, and more recently since I’ve been in a combat area.

Say – you were feeling pretty high one day at the office – weren’t you – and without liquor – I presume! The idea of telling me you have a “funny” feeling, etc. and then adding that you are not pregnant!! What a day and age! You know, dear, psychically – you might be – for – I can dream, can’t I? And that Ginsburg story! Never mind, nevermind.

Oh – I was glad to read you received the bracelet. I haven’t received your letter telling me you had received yours, but in a later letter you mention Eleanor’s receiving hers and then add that you like yours. I thought it would be too big – but the fellow who makes them insisted they are worn loose and almost over the hand. And about that German helmet – I should have thought of it myself. They’re not so easy to get now – as they were back in France when the Germans were falling back headlong, but I’ll keep my eyes open – and the 1st one I get hold of, I’ll send to him.

That’s all for the nonce, sweetheart; I’ve got to see a soldier with a possible fracture of the knee-cap – so I’ll be off. Until tomorrow, so long, dear, love to the folks – and

I got two swell letters from you yesterday – the only two the medical detachment received – by the way – and I’m getting caught up now a bit on your mail, dear. I hope mine is coming through to you a bit better too. You remark in one of your letters that “so long for now” is a G-I expression, or so you believe. I’ve always used those words, dear, and I don’t think I picked it up in the Army – but I’ve been in so damned long now – I really don’t remember a good many things about my civilian days. Do you realize, sweetheart, that you have never known me as a civilian but only as a soldier? I wonder how you’ll find me? As a matter of fact, I wonder how I’ll find myself. I guess every soldier finds himself thinking about that. It will be strange wearing different colored socks, and a tie around our necks. It’s a year since I’ve had one on – except of course when we had a pass in England. And I’m getting a little tired of this damned brownish-green stuff we wear. Every now and then I open my val-a-pac and air out my pinks and blouse; it’s so darned damp here we have to watch out for molds. They sure look fancy compared to the way we look these days. Now how did I get started on that? I’ll be crying on someone’s shoulder if I don’t stop – and I don’t really feel that way at all. You’ll marry me in uniform too – won’t you dear? I really think that once we get back to the States we’ll be de-mobilized quickly anyway.

I forgot all about the statement of mine concerning AA and the Pacific, dear. I wrote that to your mother and apparently forgot to mention it to you. And it wasn’t just a statement by a yokel – it was made by the commanding General of all AA – who happened to be on a tour over here and visited our battalion. He ought to be in a position to know. There was a time in our early days in Normandy when we were all worrying about that. There was so little of the Luftwaffe around for us to shoot at we figured we might be transferred. But later on we started getting targets and the artillery and infantry have recognized our value, I think. I’m worried more about the possibility of Lawrence having to go to the Pacific theater. I shouldn’t like that at all.

I didn’t know Red Perkins – but it’s a sad tale just the same. It’s the same old story – the folks at home are the ones that catch the most hell. That thought, incidentally dear, has always worried me more than anything else since I’ve been a soldier, and more recently since I’ve been in a combat area.

Say – you were feeling pretty high one day at the office – weren’t you – and without liquor – I presume! The idea of telling me you have a “funny” feeling, etc. and then adding that you are not pregnant!! What a day and age! You know, dear, psychically – you might be – for – I can dream, can’t I? And that Ginsburg story! Never mind, nevermind.

Oh – I was glad to read you received the bracelet. I haven’t received your letter telling me you had received yours, but in a later letter you mention Eleanor’s receiving hers and then add that you like yours. I thought it would be too big – but the fellow who makes them insisted they are worn loose and almost over the hand. And about that German helmet – I should have thought of it myself. They’re not so easy to get now – as they were back in France when the Germans were falling back headlong, but I’ll keep my eyes open – and the 1st one I get hold of, I’ll send to him.

That’s all for the nonce, sweetheart; I’ve got to see a soldier with a possible fracture of the knee-cap – so I’ll be off. Until tomorrow, so long, dear, love to the folks – and

My everlasting love is yours –

Greg

* TIDBIT *

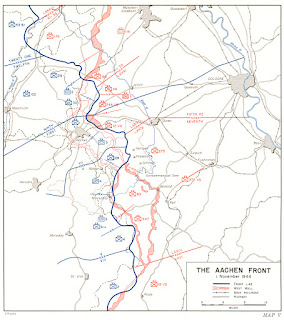

about The 28th Infantry in the Huertgen Forest

6-12 November 1944

about The 28th Infantry in the Huertgen Forest

6-12 November 1944

Perhaps the most comprehensive collection of materials concerning "The Battle of the Huertgen Forest" was found on the former "Scorpio's Website". Most of the following was extracted from various parts of that site.

Fighting on 5 and 6 November took on a confusing and fragmented pattern. Small unit engagements occurred in the zones of all three regiments. The 110th Regiment had settled into a battle of attrition with the enemy. Progress was impossible given the ferocity of the enemy resistance, the well-positioned obstacles, and the difficult nature of the terrain. Soldiers of the regiment dug in almost within hand grenade range of the enemy. Each day they received new orders to attack and each day leaders forced men from their holes. Within minutes, the advance would be halted and soldiers would return to their cold, wet foxholes. Such persistence almost completely shattered the offensive capability of the 110th.

In the north, the 109th was also subjected to strong German pressure, but managed to hold on to its positions. In this portion of the forest, it was difficult for the Germans to support their attacks with armor. The lesson for both forces was that even in this restrictive terrain, attacks without armor support had little chance of success. The Germans managed to briefly cut the only supply route into Kommerscheidt, but a small American task force of armor and infantry reopened the Kall Trail on the morning of the sixth. The situation for the 28th was growing worse by the hour. By now the regiments discarded all thought of counter-offensive operations, they were instead fighting for their lives. Incredibly, the division continued to order units to attack, few of which complied. Many of the infantry companies were now well below 50 percent strength.

The 28th had lost all offensive capability and was fighting to survive. The division began to push replacements forward; at the head of the line were the 250 soldiers that the division trained in October. Brought forward during the night, these frightened and inexperienced soldiers were put into foxholes with little or no training. As an example, on 8 November, the 2/112 (2nd Battalion, 112th Infantry), with an authorized strength of approximately 850, received 515 replacements. Even more incredibly, the battalion received the mission to attack on the following morning. It was impossible for any unit to accept such large numbers of replacements and remain an effective force. For the unfortunate replacements it was almost a case of murder. Many of them would be evacuated at each sunrise, victims of trenchfoot, battle fatigue or enemy fire.

The enemy was not the only source of casualties within the 28th. The cold and wet weather, with temperatures hovering around freezing, took a terrible toll on soldiers. Trenchfoot and respiratory infection cases skyrocketed. Many soldiers were still without necessary cold weather clothing items such as overboots, field jackets, woolen caps, and long underwear. The continual lack of hot rations also damaged the health and morale of soldiers. Rations consisted of cold K-Rations or C-Rations and many soldiers ceased eating. The situation was much too dangerous to risk bringing hot meals or drinks forward. The soldiers were also unable to build fires, since their proximity to the enemy was sure to draw rifle and mortar fire. Less than a week into the operation the division was virtually worn out as a fighting force.

On the morning of 6 November, another infantry battalion collapsed. This time it was the 2/112th, defending an exposed position along a ridge near the town of Vossenack. The battalion had been subjected to almost continuous fire from German artillery for three days. Soldiers, most of them green replacements, had become so demoralized that leaders had to force them to eat and drink. Finally, they were pushed beyond the breaking point. Imagining themselves about to be overrun, first one soldier, then another began to head for the rear. The panic became overpowering for many of the soldiers. The efforts of officers and NCO's could halt only a small percentage. There had been no German counterattack, only blind panic. The 2/112th was left with only a thin line of resistance holding half of the town. An engineer battalion rushed in to bolster the defenses. The next morning the engineers attacked and within hours cleared the remainder of Vossenack of German resistance.

On 7 November 1944 the Germans struck the 1/112th in Kommerscheidt, protected from air attack by a steady winter rain. The defenders held firm initially, but gradually began to pull back under the weight of the German attack. The 1st Battalion conducted its withdrawal in good order and managed to reestablish a weak defensive line just outside the town. The panic that had impacted the other two battalions of the 112th did not occur in Kommerscheidt. In a pitched fight, the Americans knocked out six Panzers against three M-10s and two Shermans lost.

In the middle of the fight, an erroneous message directed Colonel Peterson to report immediately to the division command post, leaving Colonel Ripple in command. The regimental commander reluctantly left the position with two men and a jeep and started down the trail that led to Vossenack. At the bottom of the draw the party was ambushed. Colonel Peterson and Private First Class Seiler were able to get away only to be cut down a few seconds later. Colonel Peterson was seriously wounded. After being left for dead, he managed to drag himself out of the draw where he was picked up and carried back to the Division Command Post. When Cota saw Peterson arrive, exhausted, twice-wounded and semi-delirious, the general fainted. Here Peterson learned that the message he had received was not sent by the Division Commaner. Who sent the message was never determined.

By noon the Germans had reduced the village. Driven out, the last Americans, with only two tank destroyers and one tank left, narrowly held on to the woods line above the Kall Gorge. By the end of the day, the defenders had been pushed from the town. The following day, this small group of infantry and armor, along with other scattered elements still on the east side of the Kall River, withdrew to the west bank. This withdrawal effectively ended offensive operations for the division. The 28th division ordered further attacks in the zones of the 109th and 110th Regiments. The units executed the attacks with little determination and achieved nothing except to add to the division's casualty totals. Finally, on 14 November, the Huertgen ordeal came to an end for the 28th Infantry Division.

The second attack on Schmidt had developed into one of the most costly US divisional actions in the whole of the Second World War. In all, the 28th Division and attached units had lost 6,184 men. Hardest hit was the 112th infantry: 232 men captured, 431 missing, 719 wounded, 167 killed, and 544 non-battle casualties — a total of 2,093.

In the north, the 109th was also subjected to strong German pressure, but managed to hold on to its positions. In this portion of the forest, it was difficult for the Germans to support their attacks with armor. The lesson for both forces was that even in this restrictive terrain, attacks without armor support had little chance of success. The Germans managed to briefly cut the only supply route into Kommerscheidt, but a small American task force of armor and infantry reopened the Kall Trail on the morning of the sixth. The situation for the 28th was growing worse by the hour. By now the regiments discarded all thought of counter-offensive operations, they were instead fighting for their lives. Incredibly, the division continued to order units to attack, few of which complied. Many of the infantry companies were now well below 50 percent strength.

The 28th had lost all offensive capability and was fighting to survive. The division began to push replacements forward; at the head of the line were the 250 soldiers that the division trained in October. Brought forward during the night, these frightened and inexperienced soldiers were put into foxholes with little or no training. As an example, on 8 November, the 2/112 (2nd Battalion, 112th Infantry), with an authorized strength of approximately 850, received 515 replacements. Even more incredibly, the battalion received the mission to attack on the following morning. It was impossible for any unit to accept such large numbers of replacements and remain an effective force. For the unfortunate replacements it was almost a case of murder. Many of them would be evacuated at each sunrise, victims of trenchfoot, battle fatigue or enemy fire.

The enemy was not the only source of casualties within the 28th. The cold and wet weather, with temperatures hovering around freezing, took a terrible toll on soldiers. Trenchfoot and respiratory infection cases skyrocketed. Many soldiers were still without necessary cold weather clothing items such as overboots, field jackets, woolen caps, and long underwear. The continual lack of hot rations also damaged the health and morale of soldiers. Rations consisted of cold K-Rations or C-Rations and many soldiers ceased eating. The situation was much too dangerous to risk bringing hot meals or drinks forward. The soldiers were also unable to build fires, since their proximity to the enemy was sure to draw rifle and mortar fire. Less than a week into the operation the division was virtually worn out as a fighting force.

On the morning of 6 November, another infantry battalion collapsed. This time it was the 2/112th, defending an exposed position along a ridge near the town of Vossenack. The battalion had been subjected to almost continuous fire from German artillery for three days. Soldiers, most of them green replacements, had become so demoralized that leaders had to force them to eat and drink. Finally, they were pushed beyond the breaking point. Imagining themselves about to be overrun, first one soldier, then another began to head for the rear. The panic became overpowering for many of the soldiers. The efforts of officers and NCO's could halt only a small percentage. There had been no German counterattack, only blind panic. The 2/112th was left with only a thin line of resistance holding half of the town. An engineer battalion rushed in to bolster the defenses. The next morning the engineers attacked and within hours cleared the remainder of Vossenack of German resistance.

On 7 November 1944 the Germans struck the 1/112th in Kommerscheidt, protected from air attack by a steady winter rain. The defenders held firm initially, but gradually began to pull back under the weight of the German attack. The 1st Battalion conducted its withdrawal in good order and managed to reestablish a weak defensive line just outside the town. The panic that had impacted the other two battalions of the 112th did not occur in Kommerscheidt. In a pitched fight, the Americans knocked out six Panzers against three M-10s and two Shermans lost.

In the middle of the fight, an erroneous message directed Colonel Peterson to report immediately to the division command post, leaving Colonel Ripple in command. The regimental commander reluctantly left the position with two men and a jeep and started down the trail that led to Vossenack. At the bottom of the draw the party was ambushed. Colonel Peterson and Private First Class Seiler were able to get away only to be cut down a few seconds later. Colonel Peterson was seriously wounded. After being left for dead, he managed to drag himself out of the draw where he was picked up and carried back to the Division Command Post. When Cota saw Peterson arrive, exhausted, twice-wounded and semi-delirious, the general fainted. Here Peterson learned that the message he had received was not sent by the Division Commaner. Who sent the message was never determined.

By noon the Germans had reduced the village. Driven out, the last Americans, with only two tank destroyers and one tank left, narrowly held on to the woods line above the Kall Gorge. By the end of the day, the defenders had been pushed from the town. The following day, this small group of infantry and armor, along with other scattered elements still on the east side of the Kall River, withdrew to the west bank. This withdrawal effectively ended offensive operations for the division. The 28th division ordered further attacks in the zones of the 109th and 110th Regiments. The units executed the attacks with little determination and achieved nothing except to add to the division's casualty totals. Finally, on 14 November, the Huertgen ordeal came to an end for the 28th Infantry Division.

The second attack on Schmidt had developed into one of the most costly US divisional actions in the whole of the Second World War. In all, the 28th Division and attached units had lost 6,184 men. Hardest hit was the 112th infantry: 232 men captured, 431 missing, 719 wounded, 167 killed, and 544 non-battle casualties — a total of 2,093.