438th AAA AW BN

APO 230 % Postmaster, N.Y.

5 May, 1945 0840

Germany

Wilma darling,

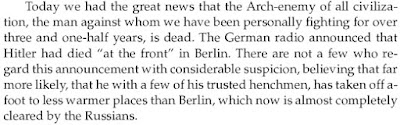

Well there’s not a heck of a lot of Germany left and I can imagine the effect at home is a good one. By that I mean that the piecemeal surrender of the Germans is assimilated better by everyone and when the fighting in Europe is entirely over – the reaction should be moderate. We here – are very behind what’s left of the war – and I can truthfully say – I don’t miss it one bit, because whether you were actually on a front line – and darling – there were times our outfit was – or whether you were a few miles back, anywhere from 2-5, – the tension was the same, as far as I was concerned; it was either the mortar shells up front, or the artillery – farther back. As far as the infantry was concerned – those I spoke with when I worked at that hospital back at Carentan – in Normandy – all said they preferred the front line – where most of the time they had to put up with land mines and rifles. They hated the artillery. No matter how you look at it though, it was a deadly choice.

But to show you how funny a war can become – last night, after not hearing any big guns for quite awhile – we were rather startled to hear some – only a couple of miles away. We contacted a T.D. outfit (tank destroyer) which is also in town – and they had already sent out a recon party. They called us back a short while later and said that they had found an outfit out on a night problem – a practice affair – and apparently a new outfit with not too much – if any – combat time. So that cleared that one up – although it seemed to us – the C.O. might have told the other outfits in town – what was going on.

Meanwhile, sweetheart, I’m still here at the ex-POW Camp and taking care of mobs of Russians. I can now ask a couple of questions in Russian – but I’ll be damned if I know the answers I get. But they all end up with some sort of pill or other and they seem quite happy about it.

There was no mail sent down for me yesterday, dear, but I hope you’re getting mine fairly regularly. I manage to have my letter to you and the folks sent up to battalion every day – and from there it gets out.

And I’m sorry I didn’t mention it before, sweetheart, but I got the biggest kick ever out of that curl of yours you sent me. I don’t know why I never thought of asking for one. You can’t imagine my reaction. It was in fact – a part of you brought so close to me. I looked and looked at it and was surprised to notice how golden it was. Before I knew it – I was building all the rest of you around it and the effect was swell. I’ve now got it in my wallet – where I hope it lasts. Gee, darling, wish I could do the same for you – but I looked over the situation very carefully, and from every point of view – and I just couldn’t see how I could do it. You understand – of course.

But honestly – it was swell – the curl – and the reaction – and as inanimate as a lock of hair can be – it nevertheless made me realize how much I want you, how much I miss you – sweetheart, how much I love you. It’s a good thing this European affair is coming to an end. Something good is bound to happen and I just hope my own particular piece of luck continues to hold out. I don’t dare think what might happen if it doesn’t –

Well, darling, again it’s time for me to go. You haven’t mentioned Mother B’s health for a long time. As a matter of fact – you haven’t mentioned the folks very much at all – of late. How are they, what are they doing etc. Send my love to them, dear – and say ‘hello’ to Mary, too.

Well there’s not a heck of a lot of Germany left and I can imagine the effect at home is a good one. By that I mean that the piecemeal surrender of the Germans is assimilated better by everyone and when the fighting in Europe is entirely over – the reaction should be moderate. We here – are very behind what’s left of the war – and I can truthfully say – I don’t miss it one bit, because whether you were actually on a front line – and darling – there were times our outfit was – or whether you were a few miles back, anywhere from 2-5, – the tension was the same, as far as I was concerned; it was either the mortar shells up front, or the artillery – farther back. As far as the infantry was concerned – those I spoke with when I worked at that hospital back at Carentan – in Normandy – all said they preferred the front line – where most of the time they had to put up with land mines and rifles. They hated the artillery. No matter how you look at it though, it was a deadly choice.

But to show you how funny a war can become – last night, after not hearing any big guns for quite awhile – we were rather startled to hear some – only a couple of miles away. We contacted a T.D. outfit (tank destroyer) which is also in town – and they had already sent out a recon party. They called us back a short while later and said that they had found an outfit out on a night problem – a practice affair – and apparently a new outfit with not too much – if any – combat time. So that cleared that one up – although it seemed to us – the C.O. might have told the other outfits in town – what was going on.

Meanwhile, sweetheart, I’m still here at the ex-POW Camp and taking care of mobs of Russians. I can now ask a couple of questions in Russian – but I’ll be damned if I know the answers I get. But they all end up with some sort of pill or other and they seem quite happy about it.

There was no mail sent down for me yesterday, dear, but I hope you’re getting mine fairly regularly. I manage to have my letter to you and the folks sent up to battalion every day – and from there it gets out.

And I’m sorry I didn’t mention it before, sweetheart, but I got the biggest kick ever out of that curl of yours you sent me. I don’t know why I never thought of asking for one. You can’t imagine my reaction. It was in fact – a part of you brought so close to me. I looked and looked at it and was surprised to notice how golden it was. Before I knew it – I was building all the rest of you around it and the effect was swell. I’ve now got it in my wallet – where I hope it lasts. Gee, darling, wish I could do the same for you – but I looked over the situation very carefully, and from every point of view – and I just couldn’t see how I could do it. You understand – of course.

But honestly – it was swell – the curl – and the reaction – and as inanimate as a lock of hair can be – it nevertheless made me realize how much I want you, how much I miss you – sweetheart, how much I love you. It’s a good thing this European affair is coming to an end. Something good is bound to happen and I just hope my own particular piece of luck continues to hold out. I don’t dare think what might happen if it doesn’t –

Well, darling, again it’s time for me to go. You haven’t mentioned Mother B’s health for a long time. As a matter of fact – you haven’t mentioned the folks very much at all – of late. How are they, what are they doing etc. Send my love to them, dear – and say ‘hello’ to Mary, too.

All my deepest, sincerest affection,

Greg

On 5 May 1945 a Japanese balloon bomb killed six people in rural eastern Oregon in a town called Bly. These six were the only World War II U.S. combat casualties in the 48 states.

Months before an atomic bomb decimated Hiroshima, the United States and Japan were locked in the final stages of World War II. The United States had turned the tables and invaded Japan’s outlying islands three years after Japan’s invasion of the U.S. naval base at Pearl Harbor.

That probably seemed a world away to a Sunday school teacher, her missionary minister husband and five students near Klamath Falls. Reverend Archie Mitchell was driving the group along a mountainous road on the way to a Saturday afternoon picnic, according to the Mail Tribune, a southern Oregon newspaper.

Teacher Elyse Mitchell (26), who was pregnant, became sick. Her husband pulled the sedan over. He began speaking to a construction crew about fishing conditions, and his wife and the students momentarily walked away. They were about a hundred yards from the car when she shouted back: “Look what I found, dear,” the Mail Tribune reported.

One of the road-crew workers, Richard Barnhouse, said “There was a terrible explosion. Twigs flew through the air, pine needles began to fall, dead branches and dust, and dead logs went up.”

The minister and the road crew ran to the scene. Jay Gifford (13), Edward Engen (13), Sherman Shoemaker (11), Dick Patzke (14) and their teacher were all dead, strewn like spokes in a wheel around a one-foot hole. The teacher’s dress was ablaze. Dick Patzke’s sister, Joan Patzke (13) was severely injured and died minutes later, the Mail Tribune wrote.

The six were victims of Japan’s so-called Fu-Go or fire-balloon campaign. Carried aloft by 19,000 cubic feet of hydrogen and borne eastward by the jet stream, the balloons were designed to travel across the Pacific to North America, where they would drop 26 pound (12 kg) incendiary devices or a 33 pound (15 kg) anti-personnel bomb with four 11 pound (5 kg) incendiary devices attached.

Made of rubberized silk or paper, each balloon was about 33 feet (10 m) in diameter. Altitude was controlled via an electric altimeter that jettisoned sandbags when the balloon dipped below 9,000 meters and vented hydrogen when it climbed above 11,000. After three days the balloon finished its 5,000 mile trip across the Pacific, a timer tripped, and the deadly payload would be released onto...whatever might lie below. Their launch sites were located on the east coast of the main Japanese island of Honshū. They landed and were found in Alaska, Washington, Oregon, California, Arizona, Idaho, Montana, Utah, Wyoming, Colorado, Texas, Kansas, Nebraska, South Dakota, North Dakota, Michigan and Iowa, as well as Mexico and Canada.

Some caused minor damage when they landed, but no injuries. One hit a power line and temporarily blacked out the nuclear-weapons plant at Hanford, Washington. Two landed back in Japan but caused no damage. American news media kept these attacks a secret during the war in cooperation with the US government to prevent fear, panic, and confusion which would fulfill the Japanese propaganda goals. The news blackout also caused the Japanese doubt about the effectiveness of their program.

Between November of 1944 and April of 1945, the Japanese released more than 9,300 balloon bombs. At least 342 reached the United States. Some were shot down. But the only known casualties from the 9,300 balloons — and the only combat deaths from any cause on the U.S. mainland — were the five kids and their Sunday school teacher going to a picnic.

Postscript: Missionary Archie Mitchell disappeared while being held captive by the North Vietnamese in 1962.

Months before an atomic bomb decimated Hiroshima, the United States and Japan were locked in the final stages of World War II. The United States had turned the tables and invaded Japan’s outlying islands three years after Japan’s invasion of the U.S. naval base at Pearl Harbor.

That probably seemed a world away to a Sunday school teacher, her missionary minister husband and five students near Klamath Falls. Reverend Archie Mitchell was driving the group along a mountainous road on the way to a Saturday afternoon picnic, according to the Mail Tribune, a southern Oregon newspaper.

Teacher Elyse Mitchell (26), who was pregnant, became sick. Her husband pulled the sedan over. He began speaking to a construction crew about fishing conditions, and his wife and the students momentarily walked away. They were about a hundred yards from the car when she shouted back: “Look what I found, dear,” the Mail Tribune reported.

One of the road-crew workers, Richard Barnhouse, said “There was a terrible explosion. Twigs flew through the air, pine needles began to fall, dead branches and dust, and dead logs went up.”

The minister and the road crew ran to the scene. Jay Gifford (13), Edward Engen (13), Sherman Shoemaker (11), Dick Patzke (14) and their teacher were all dead, strewn like spokes in a wheel around a one-foot hole. The teacher’s dress was ablaze. Dick Patzke’s sister, Joan Patzke (13) was severely injured and died minutes later, the Mail Tribune wrote.

The six were victims of Japan’s so-called Fu-Go or fire-balloon campaign. Carried aloft by 19,000 cubic feet of hydrogen and borne eastward by the jet stream, the balloons were designed to travel across the Pacific to North America, where they would drop 26 pound (12 kg) incendiary devices or a 33 pound (15 kg) anti-personnel bomb with four 11 pound (5 kg) incendiary devices attached.

Made of rubberized silk or paper, each balloon was about 33 feet (10 m) in diameter. Altitude was controlled via an electric altimeter that jettisoned sandbags when the balloon dipped below 9,000 meters and vented hydrogen when it climbed above 11,000. After three days the balloon finished its 5,000 mile trip across the Pacific, a timer tripped, and the deadly payload would be released onto...whatever might lie below. Their launch sites were located on the east coast of the main Japanese island of Honshū. They landed and were found in Alaska, Washington, Oregon, California, Arizona, Idaho, Montana, Utah, Wyoming, Colorado, Texas, Kansas, Nebraska, South Dakota, North Dakota, Michigan and Iowa, as well as Mexico and Canada.

Some caused minor damage when they landed, but no injuries. One hit a power line and temporarily blacked out the nuclear-weapons plant at Hanford, Washington. Two landed back in Japan but caused no damage. American news media kept these attacks a secret during the war in cooperation with the US government to prevent fear, panic, and confusion which would fulfill the Japanese propaganda goals. The news blackout also caused the Japanese doubt about the effectiveness of their program.

Between November of 1944 and April of 1945, the Japanese released more than 9,300 balloon bombs. At least 342 reached the United States. Some were shot down. But the only known casualties from the 9,300 balloons — and the only combat deaths from any cause on the U.S. mainland — were the five kids and their Sunday school teacher going to a picnic.

Postscript: Missionary Archie Mitchell disappeared while being held captive by the North Vietnamese in 1962.