438th AAA AW BN

APO 513 % Postmaster, N.Y.

19 July, 1945 0845

Nancy

Dearest darling Wilma –

I’m starting a little earlier than usual today because we’re having an inspection a little later in the morning and I’ll probably be busy. That’s what Com. Zone loves – inspections. It makes them feel so darned important. But I’m immune to inspection by now, and they concern me very little. The boys know how to prepare for them.

And yesterday I got some mail and just think – one from you, sweetheart, was postmarked 12 July – taking only 6 days to reach me. Gee – I can read what you wrote and I need think back only a week and I can see it all. I’m pretty certain my mail to you is taking a longer time en route because there was an article in yesterday’s Star and Stripes saying that airmail during the month of July would go by ship. When the rush is over, mail will again come by plane. I also heard from my folks and Mary. At long last it seems as if Mother A is getting a complete rest – and if it could only be a mental rest, too, I’d be happy. But with no house work, shopping etc. – there’s no doubt that she’ll be in much better health by the time the summer’s over. Now if Dad A will close his place and do the same for a few weeks, I’ll be satisfied. He’s been working hard, although he never mentions it. But I know that business inside out and with help as it’s been, I know how much running around he’s been doing.

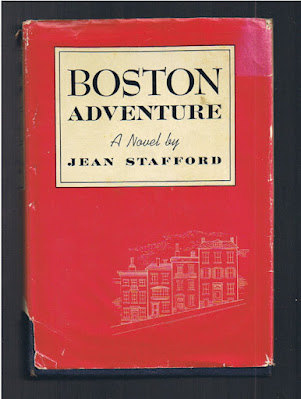

Yesterday was another quiet day here – the monotony being broken up by a game of tennis in the late p.m. I played with some Frenchmen who play a pretty sharp game and my own game is getting better as a result. The French really love the game of Tennis – and at the club there’s always a group of kids playing on their own court. I was tired – when evening came – so I took a hot bath and sat around and read. Everyone had gone out – downtown – movies, officers’ club – etc. etc. and it was pleasantly quiet. I started reading a new book – “Boston Adventure” – by Jean something or other. I don’t know yet whether or not I’m going to like it.

By the way – you wrote about Dr. Courtiss forgetting to tell his wife about a dinner party etc and then you added you’d be furious if the same had occurred to you. You wouldn’t, though, I’m pretty sure. I don’t suppose Dr. Courtiss is any more absent-minded than I am – but even in the short time I was in practice I found how occupied your mind can get over this case or that – and dinner sometimes seems unimportant – or at least is pushed out of your mind temporarily. No – it’s not a question of knowing better, dear, as you suggest. I think a doctor’s wife has really got a tough job; Just warning you, darling, although frankly I don’t think you’ll have much trouble with me – that is unless you call being kissed, hugged and loved constantly – trouble. Because that’s what I’m going to do to you, sweetheart – over and over again. Yes, an expression of love – on paper – seems empty after all these months. It never was satisfactory dear, but it has been the best substitute for the real thing – and it must have had something to it – to have kept us together all this time. And will we enjoy the real thing !!

All for now, dear. Love to the family and

I’m starting a little earlier than usual today because we’re having an inspection a little later in the morning and I’ll probably be busy. That’s what Com. Zone loves – inspections. It makes them feel so darned important. But I’m immune to inspection by now, and they concern me very little. The boys know how to prepare for them.

And yesterday I got some mail and just think – one from you, sweetheart, was postmarked 12 July – taking only 6 days to reach me. Gee – I can read what you wrote and I need think back only a week and I can see it all. I’m pretty certain my mail to you is taking a longer time en route because there was an article in yesterday’s Star and Stripes saying that airmail during the month of July would go by ship. When the rush is over, mail will again come by plane. I also heard from my folks and Mary. At long last it seems as if Mother A is getting a complete rest – and if it could only be a mental rest, too, I’d be happy. But with no house work, shopping etc. – there’s no doubt that she’ll be in much better health by the time the summer’s over. Now if Dad A will close his place and do the same for a few weeks, I’ll be satisfied. He’s been working hard, although he never mentions it. But I know that business inside out and with help as it’s been, I know how much running around he’s been doing.

Yesterday was another quiet day here – the monotony being broken up by a game of tennis in the late p.m. I played with some Frenchmen who play a pretty sharp game and my own game is getting better as a result. The French really love the game of Tennis – and at the club there’s always a group of kids playing on their own court. I was tired – when evening came – so I took a hot bath and sat around and read. Everyone had gone out – downtown – movies, officers’ club – etc. etc. and it was pleasantly quiet. I started reading a new book – “Boston Adventure” – by Jean something or other. I don’t know yet whether or not I’m going to like it.

By the way – you wrote about Dr. Courtiss forgetting to tell his wife about a dinner party etc and then you added you’d be furious if the same had occurred to you. You wouldn’t, though, I’m pretty sure. I don’t suppose Dr. Courtiss is any more absent-minded than I am – but even in the short time I was in practice I found how occupied your mind can get over this case or that – and dinner sometimes seems unimportant – or at least is pushed out of your mind temporarily. No – it’s not a question of knowing better, dear, as you suggest. I think a doctor’s wife has really got a tough job; Just warning you, darling, although frankly I don’t think you’ll have much trouble with me – that is unless you call being kissed, hugged and loved constantly – trouble. Because that’s what I’m going to do to you, sweetheart – over and over again. Yes, an expression of love – on paper – seems empty after all these months. It never was satisfactory dear, but it has been the best substitute for the real thing – and it must have had something to it – to have kept us together all this time. And will we enjoy the real thing !!

All for now, dear. Love to the family and

All my sincerest love –

Greg

Here is a Kirkus Review of Boston Adventure by Jean Stafford, published on 21 September 1944 by Harcourt Brace...

Jeffrey Scheuer offers this biography of Jean Stafford:

A strange and unusual book -- essentially sophisticated in almost a European way, and yet -- in retrospect -- the sophistication is only skin deep. The story starts when Sonia, -- daughter of German father, a Russian mother, -- is about 13, sensitive, imaginative, idealistic, in spite of the sordidness of poverty and the atmosphere of hate, suspicion, resentment at home. Sonia's ideal is Miss Pride, Boston Brahmin, who summers at the hotel on Boston's North Shore where Sonia's mother works. Sonia dreams of being taken into Miss Pride's home and eventually, after the shame of her father's desertion, the terror of her baby brother's epilepsy and death which drives her mother insane, Sonia is taken to Boston to train as secretary to Miss Pride (and to feed her sense of power). The "Boston adventure" shows the inside of Boston society, its hollowness, its pretense (a little of Marquand here), which Sonia absorbs eagerly. When Miss Pride's willful, disillusioned niece commits suicide, Sonia is caught -- held by a promise not to marry (haunted as she is by fear of her own sanity) to stay with her benefactress to her death.... A futile sort of book, with an underlying bitterness of spirit. Sonia herself never comes wholly alive -- though she tells her own story, her emotions seem derivative, unreal -- even her two ventures into romance are abortive, unconvincing, immature. But the scathing portrait of Boston's inner social circle is cruelly well done... The publishers are featuring it as their big dark horse. It will have substantial backing, people will discuss it, but many may not like it.

Jeffrey Scheuer offers this biography of Jean Stafford:

Jean Stafford, (1 July 1915 - 26 March 1979), novelist and short story writer, was born in Covina, California, the youngest of four children of John Richard Stafford and Mary Ethel McKillop Stafford. Stafford's three novels were well-received, and the first, Boston Adventure (1944), was a best-seller. But it was her Collected Short Stories (1969), which originally appeared in The New Yorker and other magazines, that earned her the Pulitzer Prize for fiction in 1970. The Pulitzer jury cited the "range in subject, scene and mood" in these bleak but elegantly crafted tales, which are often highly autobiographical. Their central characters, mainly women and adolescents, inhabit a harsh, unromantic America: a place of loneliness and loss where innocence dies hard, social convention weighs on the individual, and experience is a cruel teacher.

At age five, Stafford moved with her family from California to Colorado, where her eccentric father wrote western stories for pulp magazines under the names Jack Wonder and Ben Delight, while her mother ran a boarding house near the University of Colorado campus in Boulder. Stafford's writing weaves together the various strands of her upbringing: the natural grandeur of the West; isolation and loneliness in youth and adolescence; and her struggle against what she regarded, with a strong sense of shame, as the cramped, spiritually impoverished world of her parents. Late in her life, she would write to her sister Marjorie Pinkham: "For all practical purposes I left home when I was 7."

A series of traumas scarred Stafford's early adulthood. While attending the University of Colorado, where she earned concurrent bachelor's and master's degrees in 1936, she witnessed the suicide by shooting of her friend Lucy McKee. After a year studying philology in Heidelberg, Germany, she returned to Boulder, where she met the poet Robert Lowell at a writers' conference. And in 1938, she was severely injured in an automobile accident in which Lowell was driving, and had to undergo reconstructive facial surgery. Her only brother died in World War II. Stafford taught briefly at St. Stephens College, in Columbia, Missouri, but disliked teaching; she also worked at The Southern Review in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, and lived with Lowell in New York City and Tennessee before moving to Boston, where (despite suing him in connection with the accident) she married him in 1940.

Stafford gained overnight celebrity with the publication of her first novel, Boston Adventure, in 1944. The book is a coldly satirical account of initiation into Boston society, as seen by the daughter of a modest immigrant family. Reviews in Boston were mixed, but H.M. Jones in the Saturday Review of Literature called it "memorable and haunting," adding that "Miss Stafford is a commanding talent, who writes in the great tradition of the English novel." The New Yorker compared Boston Adventure to the work of Proust for its "ceaseless vivisection of individual experience." According to Thomas Lask in The New York Times, the novel was "mandarin and embroidered, yet it conveyed with claustrophobic exactness the ingrown, hothouse atmosphere" of its Brahmin setting. The book earned Stafford the Merit Award from Mademoiselle magazine in 1944. In 1945, she won a Guggenheim fellowship and a $1000 award from the American Academy and National Institute of Arts and Letters.

Though she spent most of her adult life in the East, Stafford never escaped the psychic tolls of her youth; literary success brought her little happiness, and her physical and emotional health remained frail. The marriage to Lowell was disastrous, and ended in divorce in 1948. In 1946-47, she spent nearly a year at the Payne Whitney clinic in New York being treated for alcoholism and depression, which would continue to plague her throughout her life. An autobiographical story in The New Yorker titled "Children Are Bored on Sunday" marked her return to writing and the beginning of a long association with that magazine, including twenty-one stories and several articles over a decade's time, and a close, thirty-year relationship with its fiction editor, Katharine White.

At age five, Stafford moved with her family from California to Colorado, where her eccentric father wrote western stories for pulp magazines under the names Jack Wonder and Ben Delight, while her mother ran a boarding house near the University of Colorado campus in Boulder. Stafford's writing weaves together the various strands of her upbringing: the natural grandeur of the West; isolation and loneliness in youth and adolescence; and her struggle against what she regarded, with a strong sense of shame, as the cramped, spiritually impoverished world of her parents. Late in her life, she would write to her sister Marjorie Pinkham: "For all practical purposes I left home when I was 7."

A series of traumas scarred Stafford's early adulthood. While attending the University of Colorado, where she earned concurrent bachelor's and master's degrees in 1936, she witnessed the suicide by shooting of her friend Lucy McKee. After a year studying philology in Heidelberg, Germany, she returned to Boulder, where she met the poet Robert Lowell at a writers' conference. And in 1938, she was severely injured in an automobile accident in which Lowell was driving, and had to undergo reconstructive facial surgery. Her only brother died in World War II. Stafford taught briefly at St. Stephens College, in Columbia, Missouri, but disliked teaching; she also worked at The Southern Review in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, and lived with Lowell in New York City and Tennessee before moving to Boston, where (despite suing him in connection with the accident) she married him in 1940.

Stafford gained overnight celebrity with the publication of her first novel, Boston Adventure, in 1944. The book is a coldly satirical account of initiation into Boston society, as seen by the daughter of a modest immigrant family. Reviews in Boston were mixed, but H.M. Jones in the Saturday Review of Literature called it "memorable and haunting," adding that "Miss Stafford is a commanding talent, who writes in the great tradition of the English novel." The New Yorker compared Boston Adventure to the work of Proust for its "ceaseless vivisection of individual experience." According to Thomas Lask in The New York Times, the novel was "mandarin and embroidered, yet it conveyed with claustrophobic exactness the ingrown, hothouse atmosphere" of its Brahmin setting. The book earned Stafford the Merit Award from Mademoiselle magazine in 1944. In 1945, she won a Guggenheim fellowship and a $1000 award from the American Academy and National Institute of Arts and Letters.

Though she spent most of her adult life in the East, Stafford never escaped the psychic tolls of her youth; literary success brought her little happiness, and her physical and emotional health remained frail. The marriage to Lowell was disastrous, and ended in divorce in 1948. In 1946-47, she spent nearly a year at the Payne Whitney clinic in New York being treated for alcoholism and depression, which would continue to plague her throughout her life. An autobiographical story in The New Yorker titled "Children Are Bored on Sunday" marked her return to writing and the beginning of a long association with that magazine, including twenty-one stories and several articles over a decade's time, and a close, thirty-year relationship with its fiction editor, Katharine White.